Mauricio González-Forero's personal website

Home / Research / Publications / CV / Funding

Human brain evolution

Brains have evolved into a stunning diversity across the animal kingdom giving rise to an even more stunning diversity in behavior. What drives brain evolution? We developed a mathematical model to help address this question (González-Forero, Faulwasser, and Lehmann, 2017). Using this model, we have found that cognitive ability and brain mass can be mechanistically related by a simple equation. Extending this model to social interactions, we have also found causal, computational evidence suggesting that human brain expansion may have been driven by ecological and cultural factors, rather than social factors such as cooperation and competition, contrasting with dominant hypotheses (González-Forero and Gardner, 2018). In a further extension of this work modelling the developmental and evolutionary (evo-devo) dynamics of hominin brain size, I have found that, counterintuitively, the sharp expansion in brain size in the human lineage may have been a by-product of selection for mature ovarian follicles, where the role of ecology and culture is not to increase selection for brain size as often assumed, but to generate a genetic correlation between ovarian follicles and brain size, a correlation that causes human brain expansion (González-Forero, 2024b). This turns out to be consistent with empirical evidence finding genetic correlations between the brain and reproductive tissues in humans (González-Forero and Gómez-Robles, in press).

The video above shows the evolutionary and developmental dynamics of the human brain as predicted by the model. The video shows the evolution of adult brain and body sizes from australopithecine to sapiens scales, the evolution of an adolescencent growth spurt, the evolution of a long childhood period, and the evolution of a doubling in adult skill level. The video is taken from González-Forero, 2024b.

How development affects evolution

The modern evolutionary synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s unified Darwinian evolution and Mendelian inheritance. Since then, many researchers have called for an analogous synthesis between evolutionary and developmental biology, arguing that the lack of such synthesis has limited evolutionary understanding.

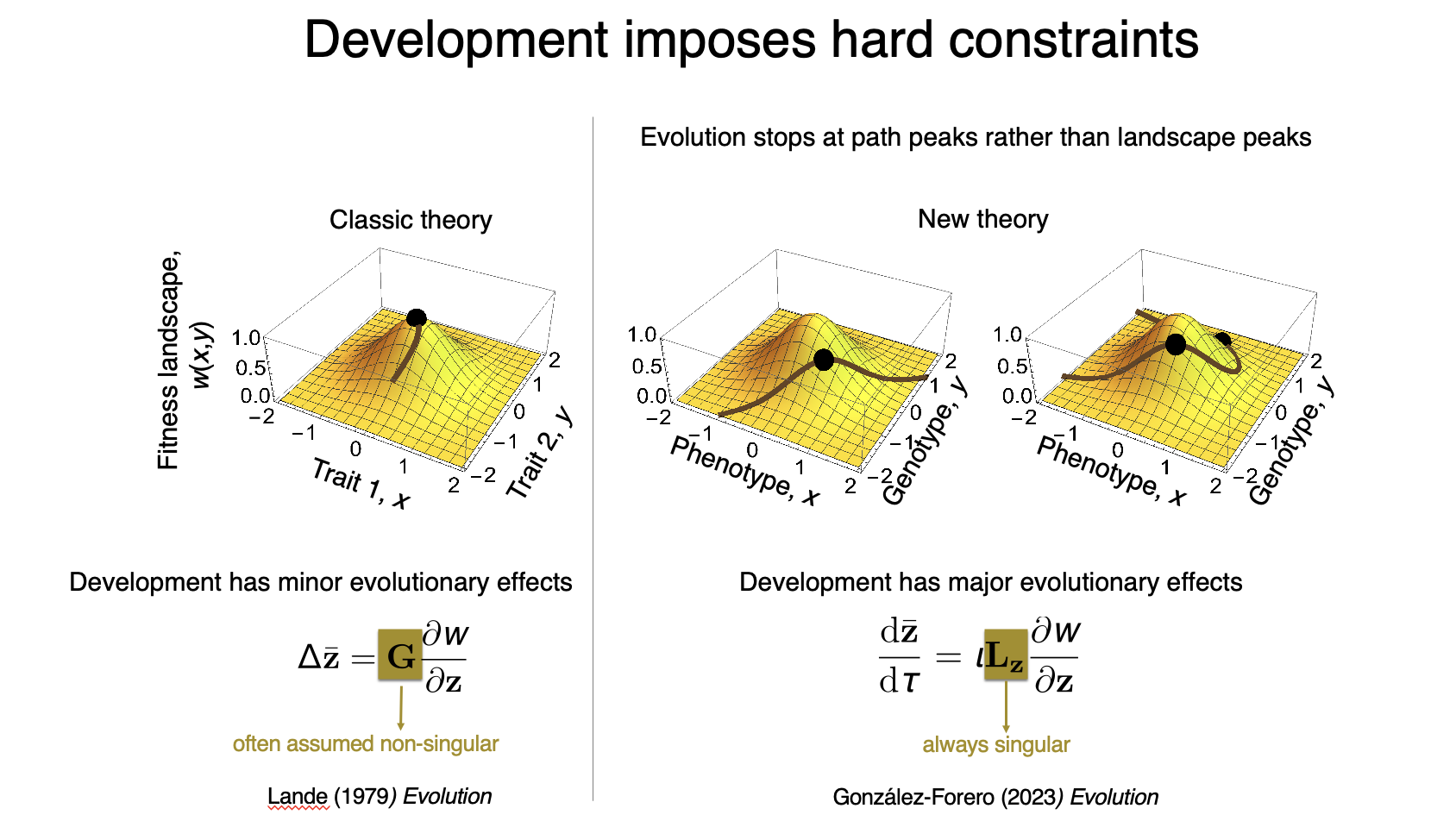

I formulated a mathematical framework that integrates evolutionary and developmental dynamics, yielding deep insights into how development affects evolution (González-Forero 2024a). The framework sharpens Wright’s principle — according to which adaptation by natural selection occurs such that the population climbs the fitness landscape — showing that development provides the admissible evolutionary path and invariably induces hard constraints on adaptation. This means that evolution stops at such path peaks rather than at the peaks of the fitness landscape as commonly assumed. Since changing development changes the path and its path peaks, this means that changing development alone changes the evolutionary outcomes even without changing selection (the landscape). Consequently, development has major evolutionary effects, contrasting with long-held views (González-Forero 2023). An important illustration of this result is that changing development alone (i.e., the path) without changing selection (i.e., the landscape) can lead to the evolution of the massive human brain size from australopithecine ancestors (González-Forero, 2024b).

The above image illustrates how development affects evolution. The left panel describes classic theory of phenotypic evolution by natural selection according to the Lande equation, where traits evolve up the fitness landscape and reach a local fitness peak; in this theory, development transiently diverts evolution by generating genetic covariation. The right pannel shows the new theory I have put together, where to describe phenotypic evolution it is necessary to describe the evolution of the underlying genotype. The genotype and phenotype are related by development, and this relationship is given by the indicated path. Consequently, there is genetic variation exclusively along that path, so evolution stops at peaks of the path rather than of the landscape. This entails that development has major evolutionary effects.

Social evolution

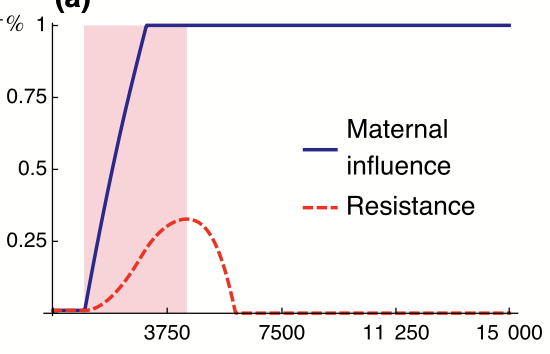

In major evolutionary transitions, groups of individuals become higher level individuals, which has had major effects on life on earth. What causes such major transitions? We have developed mathematical models to study a classic hypothesis that posits that one such major transition, i.e., eusociality, arose from ancestral maternal manipulation. The hypothesis suggests that workers in eusocial organisms evolved because mothers manipulate their offspring to become helpers. Although this hypothesis attracted interest in 1970s, evidence has since been interpreted as rejecting it because it was thought that manipulation would lead offspring to resist whereas eusocial offspring seem to help voluntarily. We have found that manipulation may evolve while resistance fails to evolve for various reasons, so eusociality can evolve from ancestral manipulation yielding voluntarily helping offspring, consistently with various patterns observed in eusocial taxa (e.g., González-Forero and Peña, 2021).

The above image (from González-Forero, 2014) shows conflict dissolution, where resistance to maternal manipulation is first selected for, but this triggers the evolution of other traits, which increases the benefit of helping so that resistance becomes selected against and disappears.

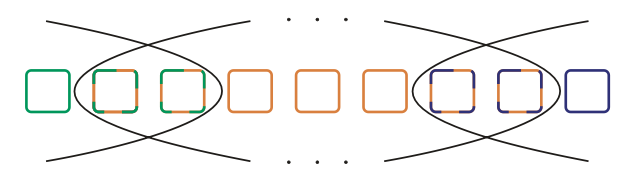

Species problem

Species are key units for evolutionary inference and conservation policies, but they are infamously difficult to define. I developed a mathematical formalization of the biological species concept and explored its consequences. During my undergraduate thesis, I found that one out of four mathematical interpretations of this concept overcomes various difficulties of the verbal concept, but in doing so populations can belong to multiple species (González-Forero, 2009).

The above image (from González-Forero, 2009) illustrates overlapping species, where each square is a population and two populations with a common color are reproductively compatible.